Governance Mechanisms

incentives linked to contractual and financial mechanisms

Keywords: Multidisciplinary, regulation, quality assurance, inspection

Care Quality Commission (CQC) - the independent regulator of all health and adult social care in England

Summary

The Care Quality Commission was established as a single, integrated regulator for health and adult social care and began operating nationally in April 2009. The need for comprehensive and co-ordinated health and social care regulation came about following concerns in recent decades of poor practices, and inequality in access and provision across the country. All health and social care providers will be required by law to register with the new regulator in order to provide services. The registration and regulation requirements that all providers must continually meet will be consistent across both health and adult social care. The approach is risk-based which means that regulation activity will be targeted where action is required. Although the CQC covers all of health and social care and not just services and structures relating to long term care, the system has the potential to regulate and monitor links and interfaces within long term care provision and safeguard and protect the rights of older people in need of care.

What is the main benefit for people in need of care and/or carers?

Direct benefits of the joining of health and social care regulation to older people and their carers is likely to be minimal. Information regarding health and socal care service performance is now held in one organisation and is potentially easier to access via the CQC website.

What is the main message for practice and/or policy in relation to this sub-theme?

The focus of the CQC’s regulation is on outcomes, experiences and human rights of people who use health and adult social care services.

Why was this example implemented?

The need for comprehensive and co-ordinated health and social care regulation came about following concerns in recent decades of poor practices, and inequality in access and provision across the country. Initiated by the Government, regulation of health and adult social care in England was carried out by the Healthcare Commission, the Commission for Social Care Inspection and the Mental Health Act Commission until 31 March 2009. The Health and Social Care Act 2008 established a single, integrated regulator for health and adult social care - the Care Quality Commission to replace these bodies. Independent providers such as primary dental care, ambulance services and GP practices are also included. The Commission was created in shadow form on 1 October 2008 and began operating on 1 April 2009.

The new system will create a joined-up ‘single system’ regulation for health and social care with the aim of ensuring better outcomes for the people who use services. Although the CQC covers all of health and social care and not just services and structures relating to long term care, the system has the potential to regulate and monitor links and interfaces within long term care provision and safeguard and protect the rights of older people in need of care.

Description

A new set of regulation requirements, priorities and guidelines were put in place in April 2010 following a large scale public consultation which was driven forward by the Government. These focus on outcomes, experiences and human rights of people who use health and adult social care services. CQC’s functions are concerned with assuring safety and quality, assessing the performance of commissioners and providers, monitoring the operation of the Mental Health Act 1983 and ensuring that regulation and inspection activity across health and adult social care is coordinated and managed. All health and social care providers are required by law to register with the CQC in order to provide services. The registration requirements that all providers must meet are consistent across both health and adult social care. The approach is risk-based which means that regulation activity will be targeted where action is required.

A summary of CQC powers and duties:

- Registering providers of health care and social care to ensure they are meeting the essential standards of quality and safety.

- Monitoring how providers comply with the standards by gathering information and visiting them/inspecting when needed.

- Using enforcement powers such as fines and public warnings if services drop below the essential standards, including closing a service down if patients are at risk.

- Protecting people whose rights are restricted under the Mental Health Act.

- Promoting improvement in services by conducting regular reviews of how well those who arrange and provide services locally are performing.

- Carrying out special reviews of particular types of services and pathways of care, or undertaking investigations on areas where there are concerns about quality.

- Seeking the views of people who use services.

The CQC uses a number of tools for regulating service provision and commissioning:

- Essential Standards of Quality and Safety: 28 regulations and associated outcomes which inspectors check for compliance.

- Quality and Risk Profile: data gathering tool.

- Provider Compliance Assessments: enables providers to check themselves against the regulations.

- Annual Quality Assurance Assessment: self-assessment completed by adult social care providers.

- Judgement Framework: for inspectors to judge compliance with regulations in relation to risk.

- Quality Rating: scale of 0 (poor) to 3 (excellent); ratings denote the amount of times an inspection is required – 0=twice yearly and 3=once every three years.

- Commissioner Assessment which assesses the quality of health and adult social care commissioning from Primary Care Trusts and Councils.

If the above tools identify risks to users, then the CQC will take steps to enforce improvement.

There are a number of incentives for agencies to improve the delivery of their care, however, the regulation system remains somewhat punitive with severe repercussions and penalties for those whose quality of care and patient safety is lacking.

CQC budget for 2010/11 is £161.2m/€190.2m) (total recurring revenue cost), a proportion of these resources are derived from registration fee income (£5,000/€5,900 per service), and the remainder is made up of grant-in-aid from the Department of Health (£63.8m/€74.3m). There will be an annual fee charged to NHS providers for regulation, ‘banded’ according to number of beds or income. For example, an acute provider with 0-250 beds will pay £15,000/€17,700; another provider with gross operating costs of over £1 million will pay £60,000/€70,800. CQC has a total staffing of 2,081 full-time equivalents. A model for the operations directorate involves regions delivering all main regulatory activities: registration; monitoring compliance and assessing performance, but with specialist nationally-based advice for registration, enforcement and provider relationships. There are also national operations delivering specialist statutory functions and joint inspection with other regulators (i.e. Ofsted, Youth Offending Teams). There is strong partnership and sharing of responsibilities between organisations to provide interfaces between operations staff and managing data/handling intelligence. The operations model has so far registered 378 provider trusts and it plans to register over 12,000 adult social care and independent healthcare providers, covering some 24,000 services.

What are/were the effects?

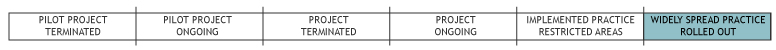

The effect of the regulations and outcome measures were only put into place in April 2010 and have not yet been fully implemented, therefore their success and effectiveness is unknown, particularly in long term care. However, there are feedback mechanisms in place from providers and users that will feed into reviews and provide information on how the regulations are working. The changes have so far been systemic and are mainstream as all health and social care providers and commissioners must be registered with the CQC, but it is so far untested. In terms of resources used compared to the previous three organisations which it replaced, thus far the CQC have reduced the number of offices from 23 to 8, workforce from 2,900 to 2,100 and budget from £240m to £164m (€283m to €194m).

Inspection reports are available for public viewing via the CQC’s website. Thus service users are viewed as consumers of health and social care services who can select which services they choose to access based on performance. A negative consequence of the publication of quality reports for services is that any severe failings may be picked up by the media and the service’s public image may suffer for it.

In addition CQC are collecting a wealth of information about providers and are using this with their partner organisations to give illustrations of best practice and to develop training programmes. There is also a Regional intelligence and evidence officer who will interface with CQC to develop ways of data dissemination and evidence building.

What are the strengths and limitations?

Strengths

- Regulations/standards and outcomes have a strong grounding in user involvement.

- The new regulations recognise movement between services and so there is greater potential to monitor links and interfaces between services in LTC systems.

- CQC reports on services and organisations are made public and thus enable users to make decisions about service use through the ratings system. This is particularly important for those needing care homes.

- CQC have information sharing agreements with a range of other regulators and organisations so that duplication is minimised.

- Organising both health and social care regulation under one regulatory body indicates equal importance of monitoring health and social care.

Weaknesses

- CQC provide detailed outcomes and prompts for each regulation, but providers are not legally bound to use these and so they are not enforceable. This is so that innovative services that want to provide alternative ways of meeting standards are able to do so without being penalised.

- Services which do not provide ‘regulated activities’ do not have to register with CQC and therefore are unregulated. The definition of ‘regulated activities’ is complicated particularly when it comes to ‘nursing care’ and there is potential for poor practice to fall through the net. For example, where a person makes their own arrangements for the regulated activities of ‘nursing care’ or ‘personal care’ in their own homes and an individual nurse or carer works directly for them, the nurse or carer does not need to register to provide that service and there do not appear to be any standards to regulate the quality of informal care.

- Assessment of organisations is largely self-report. While this may save the regulating body money, it increases the workload on care providers. In addition there is the potential for self-assessment to be more favourable than may be the case. This is particularly so as there is considerable pressure not to have an unfavourable review.

Opportunities

- Research on services also plays a part in ensuring quality in care. The CQC carries out studies in order to provide guidance on best practice and publishes regular best practice examples. The mass of information to be collected will serve as important information upon which to develop good practice and support organisations in implementing improvements in the future.

- National metrics, or quality indicators, are currently being developed. Quality indicators for acute settings have been published, and indicators for community services will be developed over the next year (Darzi, 2008). NHS organisations will be asked to develop their own additional indicators to meet their local needs.

- From 2010 NHS will have to publish ‘Quality Accounts’ which will reflect patient safety, experience and outcomes. The comparative information will be available on the NHS Choices website. It is unclear though whether these indicators monitor across services or just measure the performance of a singular service.

Threats

- As with all government bodies, there are significant on-going changes within the structure of CQC, staff reductions etc which may have an impact on the ability of the organisation to deliver the big regulatory agenda. There are other partner organisations which are set to be disbanded which may limit the opportunities of information sharing.

- Historically, previous regulation systems have missed serious problems with care within organisations that were favourably reviewed and rated, so there may be the potential for this to happen in the new regulatory system.

Credits

Author: Jenny Billings / Laura HoldsworthReviewer 1: Kai Leichsenring

Reviewer 2: Teija Hammar

Verified by:

External Links and References

- Archer, B. (2009) Clinical Quality Indicators Development: Indicators Survey Report.

- Darzi, A. (2008) High Quality Care for All – NHS Next Stage Review. Final Report.

- Care Quality Commission (2010) Focused on Better Care: Annual report and accounts 2009/10. London: TSO.

- Health and Social Care Act 2008

- Quick guide to Essential Standards

- Quality and Risk Profiles