Assessing needs

older peoples’ and/or informal carers’ rights: information, shared decision making, consent, privacy regulations, complaints, second opinion

Keywords: social integration and rights, older people empowerment, neighbour solidarity, needs assessment

Neighbourhood Solidarity

Summary

The Neighbourhood Solidarity concept is a local project that started in 2003 in Lausanne. The programme thus was gradually implemented in several neighbourhoods and towns of the Swiss French speaking canton of Vaud. The underpinning philosophy of the programme was to use a method that would help vulnerable older people to remain at home to improve the quality of their life, foster the integration of older people in their neighbourhood and enable informal carers to cope with the difficult situations they are facing. To achieve these goals, finding new ways for ‘reinforcing neighbourliness’ was deemed essential.

What is the main benefit for people in need of care and/or carers?

The main assessed impact is for older people to be integrated and in control of their daily life in their neighbourhoods.

What is the main message for practice and/or policy in relation to this sub-theme?

The example will describe the specific method that was used for older people to be more active in their living environment: by enhancing their capacity to integrate and find a solution to the issues they are facing; to assess their related needs and be involved in any decision making process. This project should give the opportunity for others to learn how to help older people make the best use of their existing resources.

Why was this example implemented?

The project addresses gaps such as isolation of older people, lack of cohesiveness between younger and older people, and difficulties that families and relatives have in dealing with informal care on their own. The rationale was to help isolated older people become or remain in control of their daily life through an improved integration of formal networks (such as home care organisations) with the local informal networks (neighbours, families). The chosen method aimed to help the various inhabitants of a neighbourhood to become ‘change agents’, showing them how to live together by pooling and using their available resources more efficiently. Its underlying concept is based on the methodological approach of ‘community health’ of The Théophraste Renaudot Institute which states that when members of a community are brought together in order to reflect about their health/ social problems and related needs, they can then build the actions to address the problems together. The programme is based on the principle of action-research (Barbier, 1996), which states that when a problem is identified by a community's stakeholders (political authorities, local institutions or individuals), they must jointly find the ways and means to solve it by themselves (Genton, 2008:16). It offers a framework to help communities identify what the main issues are according to their life experiences and put forward the most appropriate solutions. So the project is an instrument for social intervention that aims to actively get the neighbouring inhabitants together in order for them to support initiatives that will assist frail older people.

Description

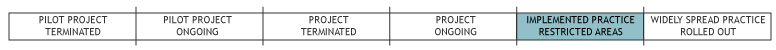

'Quartiers solidaires' begun in 2003. The project initiators were Pro Senectute (the largest professional organisation serving older people in Switzerland) and it was developed by Pro Senectute Vaud (project leader) and the Lausanne local authority, which signed a collaboration agreement. The pilot project began in 2002 in a Lausanne neighbourhood of 4,700 inhabitants (2006 statistics). In 2004, it was implemented in another municipality (10,750 inhabitants close to Lausanne) and then extended in another neighbourhood of Lausanne (2,400 inhabitants). Finally, in 2006 the project spread out to a neighbourhood with more than 2,000 inhabitants of another town in the same canton. The Leendaards Foundation, which is active in the social, cultural and scientific fields in the cantons of Vaud and Geneva, financed the research and evaluation components of the project. Other foundations financed the start of this project, then public funds partly financed each neighbourhood. The Confederation pays a fixed amount. Municipalities pay 80% of the project developed on their territory. The canton pays 20% of each project and ensures a supplementary amount for other financial burden.

The programme methodology

For each project one social worker, one trainee and one methods specialist are recruited. The process of developing the project takes place in four steps:

- Exploration: the social worker conducts an initial investigation in order to assess the needs and resources of the inhabitants. For this, like an ethnographer, he positions himself as a member of the neighbourhood in order to assess the number of older people and the structural resources in the area (like social and medical care structure, shops, banks, meeting places, etc.).

- Construction: the social worker organises community forums for older people and their relatives that aim to identify problems and assess related needs. The forums are used as a ‘think tank’ for finding solutions.

- Implementation: projects that have been selected during the forum are developed by the social worker and with neighbourhood volunteers. For example, in one neighbourhood, every Monday three retired people organise meals for 30 older people. Also, a café is opened and manned by retired people one morning per week.

- An evaluation of the nature of the project and the implementation process. For a more detailed description: Quartiers Solidaires - Mieux vivre ensemble.

What are/were the effects?

An evaluation was carried out after a four year development period. It used indicators such as satisfaction of older people in the neighbourhood, the extent to which certain social competencies had increased, the degree of solidarity within the area, and how the process developed (Fondation Leenards, Pro Senectute Vaud, n.d.).

The sustainability of the project was seen to be related to the extent to which the following outcomes were achieved:

- creating meaning and social links in a neighbourhood

- making older people become more involved in the community

- how the project succeeded in alleviating tasks carried out by traditional social services and older people's relatives and families.

The evaluation showed that solidarity and participation of older people in neighbourhood life had increased: social contacts of beneficiaries have improved and older people are more involved in social activities (See Genton, 2008). Individual welfare and the overall quality of life of the community have also got better. Strengthening social links by solidarity networks enhances peoples’ pleasure with meeting each other. The project makes it easy for people to socialise, raising self-confidence and the desire to change. Also as institutions are increasingly integrating the program and introducing other activities such as conferences and debates, better interaction between inhabitants and professionals is promoted. The social worker can also be part of the group and give his/her help in different types of situations. The evaluation process has helped to identify strengths and weaknesses. The method also encourages the wishes of the inhabitants to be acted upon.

What are the strengths and limitations?

Strengths

- The project provides a unique opportunity to motivate and support communities working together for the greater good of its inhabitants, especially older people, and to counteract isolation.

- The project helped to shed light on the hitherto ‘invisible’ needs of older people and reveal their own point of view.

- The method was also not complicated and constructed in such a way that people were easily able to take part and respond.

- Retired people being involved in the organisation of several activities are able to gain ‘social capital’ from their involvement. This is connected to improved health.

Weaknesses

- More focus should be given to reaching the more isolated people who, for many reasons, have limited contact with the community.

Opportunities

- This project complements public medical and social programmes. It works against social exclusion of older people by helping them to participate actively in community life.

Threats

- According to the evaluation report of the project (Genton, 2008), there is a risk of promoting a ‘result culture’ where institutional partners may use and orientate the project for their own interest which may not be aligned with the ones of the target population.

- Project leaders should be cautious about replicating interventions and actions in similar communities and ensure that specific issues unique to individual neighbourhoods are addressed. This aim of the project is to enable the inhabitants of the neighbourhood to sustain the project.

- However, the project is at risk of failing when the social worker leaves if the local dynamic is not strong enough.

Credits

Author: Marion Repetti, Haute Ecole de Travail Social et de la Santé Vaud (http://www.eesp.ch/)Reviewer 1: Barbara Weigl

Reviewer 2: Laura Cordero

Verified by: Pro Senectute Vaud (http://www.vd.pro-senectute.ch)

Links to other INTERLINKS practice examples

External Links and References

- Barbier, R. (1996) La recherche-action. Paris: Anthropos.

- Fondation Leenaards

- Fondation Leenards, Pro Senectute Vaud (N.d.) Quartiers Solidaires: Mieux vivre ensemble. Lausanne: Pro Senectute Vaud, Fondation Leenaards.

- Fondation Renaudot (n.d.) Pratiquer la santé communautaire.

- Genton, A. (2008) Quartiers solidaires: exploration d'un pari communautaire. Rapport de recherche. Lausanne: Pro Senectute Vaud, Fondation Leenaards.

- Pro Senectute Vaud