Governance Mechanisms

institution building to support and emphasize LTC as a specific area of concern

Keywords: care in the community, funding, intermediate care, integrated care, nursing agencies

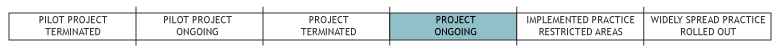

Governing the process of change of the funding scheme of Community Nursing Agencies (CNAs)

Abstract

This French example describes the process steered by the Ministries of Health (MOH) and Labour (MOL) to change the way Community Nursing Agencies (CNA) were financed.

Community Nursing Agencies (CNAs) are mainly staffed with salaried nursing assistants and employ ‘free’ nurses under contract paid by their employer on a fee for services basis. Some of them may also employ social workers (SPASAD). The specific objective of the new scheme was to enhance the capacity of the agency to deliver integrated personal and technical nursing care in the home setting as needed by a distinct section of frail older people (target population). According to the (still ongoing) funding scheme, community CNAs are funded on the basis of a ‘flat per capita tariff’ which does not allow them to care for the target population without being at financial risk. In order to find a more appropriate funding scheme, a three step process was set up. First, on behalf and under the supervision of two central divisions of the Ministry of Health, a survey using an ad hoc sample (2178 patients cared for within 36 CNAs) was conducted in 2007, in order to identify potential factors explaining the wide variations in patients’ costs of services when delivered by CNAs. Accordingly, a needs based resource allocation method was set up relying on a relative value scale resulting from statistical modelling. Two exhaustive surveys on CNAs’ management of patients, conducted in 2008 and 2010 confirmed the sample based results that a needs based funding system would be fairer and more efficient in budget allocation. The way to apply the new scheme (setting the price level according to the relative value scale) is still debated but the reform is expected to be shortly adopted by the government.

What is the main benefit for people in need of care and/or carers?

People with intermediate care needs, i.e, needing coordinated home help, personal and nursing care, can now be treated at home by Community Nurse Agencies (CNAs) as the new scheme does not make the agencies financially at risk when they care for the target population.

There is an extra benefit for informal carers as CNA services are more flexible than when delivered by Hospital at Home (HAH-OP), thus allowing a better balance between caring and living their life.

What is the main message for practice and/or policy in relation to this sub-theme?

At the policy level, the example shows that when trying to change a funding scheme (of CNAs in this case), a well-designed scientific study, actively involving all stakeholders may help the change process by bringing more evidence in the debate. This will be useful as the new scheme is expected to provoke tough discussions because it will result in ‘winners and losers’.

At the practice level, it shows that it is possible to build a new funding scheme based on needs and allow a more efficient use of the CNAs. This facilitates the gap to be bridged between Hospital at Home agencies (HAH-OP) and regular home care agencies for older people, while favouring the development of more integrated social and health care.

Why was this example implemented?

This reform is part of a larger LTC policy called ‘Home maintenance policy’ in order to respond to older people’s desire to remain in their homes, as well as tackling the issue of enhancing the volume efficiency and appropriate delivery of integrated social and health care. So care for frail community dwelling older people becomes more responsive to need and at the same time contains hospital expenditures.

In France, there is a gap in services for older people with intermediate LTC needs who require a mix of personal and technical nursing care. This is because the target population’s type and level of care is too high and does not fit the ‘home care agencies’ skills, which are only equipped to deliver basic care (ADL/IADL); and due to the fact that this level of care is costly when provided by Hospital at Home agencies (HAH-OP). CNAs had the human and technical resources to deliver this type of care but their services were paid according to a flat rate per capita. As this scheme did not account for the differences in patients’ costs according to care needs, they were at financial risk in cases where the target population accounted for a large share of their caseload. The new tariff reform of Hospital at Home (HAH), as applied since 2005, filled only one part of the gap between in-patients (hospital/residential) care and home care, as the tariff was set up to cater for older people with high and/or complex levels of need. So in 2007, the Minister for Health and Solidarities and the Minister Delegated to Social Security and Older People issued a document stating that they wanted to improve the organisation and the joint management of elderly patients between the Hospital at Home (HAH-OP) and the Community Nursing Agencies (CNAs). An ad hoc study would be set up to identify suitable patients in terms of physical and environmental characteristics and their care support needs, who would be cared for by CNAs according to their skills and expertise, and that a new funding scheme needed to be set up.

Description

Because CNAs employ nursing assistants who deliver personal care, while technical care (via medical instruction) is delivered by nurses, they are potentially able to deliver care to older people who need a mix of integrated personal and technical nursing care. CNAs intervene at home (96%) as well as in nursing homes, and their development is regulated at regional and national levels by respective plans. In the prospective 2007 budget of the National Health Sickness Funds (ONDAM) the average ‘annual cost per place’ was fixed at €10,500 corresponding to €30 per day per patient (flat rate).

The Ministry of Health (MOH) and of Labour (MOL), under the supervision of their respective central division (DGOS – General Department of Health Care Organisation); DGCS – General Department of Social Cohesion), set up a team of researchers from two health economic research centres (URC-Eco IDF and IRDES) and members from the National Health Sickness Funds. The purpose of their study was to develop a new funding scheme for CNAs to provide care delivered by nurses and social workers (ADL and IADL linked services), thus excluding other medical or technical nursing care. This new scheme was based on the results of a clinical and cost survey that was launched in 2007 to collect data on 2,178 patients cared for within 36 CNAs (Chevreul, 2009). These data allowed both CNA’s ‘care load’ in terms of patient’s needs (level of dependency, deficiencies, diseases, type of care) to be described; and allowed a differentiation to be made between patients with only basic care needs (personal care) from those also needing technical nursing care. An estimate of CNAs’ overhead costs was performed. Using a micro-costing approach and hierarchical modelling, the main factors explaining variations in patients’ costs were identified. The cost model retained 14 explanatory factors describing patients’ ‘disease burden’ and disability level (as measured through the AGGIR assessment tool), but also included help provided by informal carers.

Two exhaustive surveys (2008, 2010) of patients cared for by CNAs conducted at a national level confirmed the results coming out of the 2007 sample based survey. It showed that, when funded according to the present scheme, on average CNAs with a higher need case mix were below their financial ‘bottom line’ while those with a lighter case load where above. This gave more evidence that a needs-based payment model was required.

According to a new resource allocation scheme, CNAs would receive a fixed amount for overhead costs, and would be paid direct costs by tariffs based on the cost of their patient’s needs, so according to their ‘care load’. Several financial incentives were also inserted. This included higher payments (than set by the model) for patients with high levels of need in order to favour their uptake instead of being cared for by HAH-OP; and lower payments for patients with low levels of need in order to favour care substitution by less costly home care agencies.

In order to set up the reform, MoH and MoL are currently negotiating the level of the different tariffs with all stakeholders (as only a relative value scale has been set up) and thus are debating about the value of the conversion factor and the tariff basis (value 1 in the RVS).

What are/were the effects?

At the end of 2008, there were 2,095 CNAs providing care to 93,000 older people (95% of their patients) for a cost amounting to over €1 billion per year (DREES et al., 2010). The 2010 survey showed that while the level of the overall budget dedicated to fund CNAs could be considered as appropriate, individual budgets were not well allocated: average estimate annual costs of care per patient (€10,525) was very close to the annual prospective per capita budget (€10,878) but wide variations existed across patients’ costs, ranging from one tenth to three times the flat rate. This variation explained why some agencies with a ‘heavy care load’ were short of funds while others could be considered as ‘over funded’. The research showed that applying the new funding scheme would result in a fairer and more efficient allocation of resources as CNAs would receive funds in relation to their case load.

A rapid survey (2010) also showed that the target population of older people living at home with needs requiring coordinated care experienced a better quality of life, as services delivered by CNAs were considered more flexible than when delivered by HAH-OP.

What are the strengths and limitations?

Strengths and opportunities

- The CNAs relative value scale constitutes a basis for a fairer allocation of funds between CNAs without overall extra cost: CNAs will receive higher remuneration when they care for patients with high levels of need and a lower remuneration when they care for patient with lower levels of need.

- A better use of CNAs’ workforce can delay hospital admissions and allow for earlier/safer hospital discharge.

- The new scheme enhances care continuity not through integration within CNAs’ teams (which existed previously) but through a better coordination with other care providers. This is because some CNAs are managed under the same organisation as HAH-OP structures, so a patient may keep the same nurses even when his medical condition and care needs increase.

- It could allow for a better planning of CNAs according to patients needs, at regional (5) and national levels (6).

- It facilitates a more transparent negotiating process, as there is now more evidence about needs and related costs.

- Incentives or disincentives inserted in the remuneration scheme in order to improve the ‘allocation efficiency’ of the overall health and social system through a better channelling of patients is a strength, as it allows for less costly interventions both for patients with high and low levels of need.

Weaknesses and threats

- At the political level, this new needs and activity based relative value scale of CNA’s patients still has to be transformed in a national funding scheme by fixing the conversion factor and setting the basis of the RVS. This entails hot debate with CNA’s but also with free nurse’s Unions as even if CNAs’ overall budget is not going to change, there will be winners and losers (both at organisational and individual level) in the new system.

- At an organisational level, the CNAs will have to be equipped with microcomputers and internet in order to collect all the data needed to calculate the tariffs of each patient.

- Regarding human resources, CNAs’ staff training and time spent for reporting will entail extra costs.

- Sickness Funds will need to develop controls in order to avoid patients being wrongly coded in order to charge higher costs (‘coding creep’).

- As for HAH-OP, as informal carers will get older whilst the cared-for people may need more care, they may be unable to continue to care. Thus a specific support policy for informal carers will also be needed.

Credits

Author: Laure Com-Ruelle & Michel NaiditchReviewer 1: Jenny Billings

Reviewer 2:

Verified by: Laure Com-Ruelle, IRDES

Links to other INTERLINKS practice examples

External Links and References

- Chevreul, K. (ed.) (2009) Les patients en services de soins infirmiers à domicile (SSIAD) – Le coût de leur prise en charge et ses déterminants. Paris: Ministère du Travail, des Relations sociales, de la Famille, de la Solidarité et de la Ville/Direction générale de l’action sociale.

- SSIAD (CNA) en France: Code de l’action sociale et des familles, article L. 312-1, 6e et 7e.

- Decree n° 2004-613 (25 June 2004)

- DREES et al. (2010) Les services de soins infirmiers à domicile en 2008. Paris: DREES et al. (Etudes et Résultats n° 739).