Policy

policy barriers and opportunities in terms of linking social and health care

Keywords: health and social care integration, joint working, collaboration, commissioning, integrated provision

Care Trusts – structural integration of health and social care

Summary

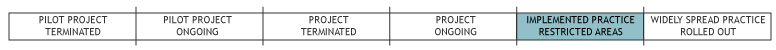

England has two separate systems for delivering health care and social care (with longstanding attempts to promote more effective joint working across this divide). In 2000, a national government policy document (The NHS Plan) set out brief proposals for a new type of health and social care organisation – a Care Trust. This could either be a provider organisation or a local organisation that both commissioned and provided integrated care, and was based on a traditional NHS model (with social care powers and responsibilities essentially being delegated to the NHS). Perhaps because of this there were only ever very few Care Trusts (a maximum of 10 out of about 150 health and social care communities across England), with local councils often seeing this as a form of NHS ‘take-over’ of social care. Some areas also considered Care Trust status but decided that formal structural integration would not produce more benefits than a less disruptive form of joint working. Despite this, the Care Trust model remains interesting as the most structurally integrated approach to joint working across health and social care in England.

What is the main benefit for people in need of care and/or carers?

It is difficult to link positive outcomes for older people in localities directly to the ‘care trust’ joint structures. Although many areas with care trusts have had positive results these could be equally attributed to other factors.

What is the main message for practice and/or policy in relation to this sub-theme?

Developing joint organisational structures between health and social care may lay down a useful structure for future work. However, evidence suggests that more bottom-up approaches by local actors are also needed to complement such structural changes.

Why was this example implemented?

In England, the post-war welfare state that was introduced from the 1940s onwards created two separate systems for people who were seen as ‘sick’ (defined as having ‘health’ needs met free by the National Health Service or NHS) and people who were frail or disabled (who were seen as having ‘social care’ needs met by local authority social services and often attracting user charges). Out of this has arisen two separate systems for providing health and social care, with different geographical boundaries, budgets, legal frameworks and cultures. This is despite the fact that people using services – especially frail older people – rarely distinguish between health and social care needs – they simply have ‘needs’.

In response, joint working between health and social care has long been a policy aim (at least since the 1960s and 1970s) – although this acquired increased impetus with the election of the New Labour government in 1997 (with a commitment to ‘joined-up solutions to joined-up problems’). Initially, the new government sought to promote inter-agency collaboration in more bottom-up ways (see linked practice example around the Health Act 1999) – but with a new Secretary of State for Health the Care Trust policy sought more formal and structural approaches to integration.

Description

Care Trusts are local NHS organisations either providing or both commissioning/providing integrated health and social care. Many of the early Care Trusts were mental health provider organisations, but more recent Care Trusts are ‘Primary Care Trust-based’ (that is, they both commission and provide integrated health and social care) and focus on all adult service users (many of whom are older people in practice). Although each Care Trust varies, this has often meant that adult social care staff transfer their employment to the Care Trust, that terms and conditions are harmonised, that the Care Trust manages an integrated health and social care budget for the local population and that integrated health and social care teams are established.

The choice of forming a Care Trust was left to local areas that felt this was the best way forward for local services. Thus, local health and social care leaders would decide (after consultation) if a Care Trust was the best way forward for local people/services, and submit a formal application to the government to adopt this new organisational form. The underpinning legislation essentially involves the local authority delegating its funding, responsibilities and staff to the new Care Trust, which is then responsible for commissioning/delivering both health and social care. Accountability to the local authority is often achieved via a partnership agreement, where the Care Trust commits to achieve certain social care-related targets or a particular level of performance, and has to report regularly on these to the local authority.

In practice, integrating separate structures has taken a number of years and raised a series of practical issues (for example, pensions, terms and conditions etc) as well as organisational development/cultural issues (for example, the difficulty of combining ‘medical’ and ‘social’ models of mental distress in a mental health Care Trust or of bringing together different health and social care professionals in a Primary Care Trust-based Care Trust). As one practical example, one Care Trust seeking to set up multi-disciplinary teams and a single assessment process found that nurses were uncomfortable asking questions about people’s finances; the social workers were used to this but felt uneasy asking about people’s bowel and bladder management.

What are/were the effects?

This is difficult to pinpoint. Care Trusts have never been formally evaluated and so many other policies have been developed with similar aims that it is difficult to attribute any positive developments to Care Trusts per se. While one Care Trust in particular has demonstrated impressive results around reductions in use of emergency hospital beds for local older people, other Care Trusts have not achieved similar results – and so the impact of changing organisational structures remains unclear. It is possible that the one high-performing Care Trust is high-performing for reasons other than being integrated (for example, strong leadership and vision for the local area, a strong local identity and a positive history of joint working). Indeed, early monitoring by the Health Services Management Centre suggested that the early Care Trusts were often in areas where there had been stable, shared boundaries over time, continuity in senior management and a long history of joint working – and these factors do not necessarily apply to other health and social care communities. Informally, Care Trust leaders could not identify any major outcomes for service users that could not have been achieved with a less disruptive form of partnership – but felt that they may have laid the groundwork for future high performance. Unfortunately the policy context has continued to change significantly throughout this time, so it remains difficult to test this in practice.

What are the strengths and limitations?

There have only ever been a small number of Care Trusts, with many areas exploring less disruptive forms of joint working. The existing Care Trusts have also seemed a little isolated at times – despite initial policy claims that all services for older people would be provided by Care Trusts in time, policy now seems to have moved on and does not seem to take account of the unique nature of Care Trusts.

- Some Care Trusts were also formed in very small health and social care communities that may well have lost their local health services to a bigger neighbour in previous reorganisations, with integration being seen by some as a way of achieving economies of scale locally in the face of external threat (that is, local health organisations chose to integrate with local social care partners in order to retain control of local services, rather than risking their health services being taken over by a larger organisation with different priorities and focus).

- Many current Care Trusts also say that this was the right model for them at the time, but that joint working has been a much longer-term journey for them (with Care Trust status simply the latest in a long history of joint working). Thus, one Care Trust feels that it began working across the health and social care divide in the 1970s, using whatever policy mechanisms emerged over time to improve and deepen local relationships. For them, Care Trust status was merely the latest such policy, helping to move relationships forward and to add momentum, but not creating joint working from scratch.

- Some commentators have also emphasised the limitations of structural change as a means of delivering joint working (at least in the short- to medium-term).

Credits

Author: Jon GlasbyReviewer 1: Laura Cordero

Reviewer 2: Ricardo Rodrigues

Verified by:

Links to other INTERLINKS practice examples

- Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA)

- Section 75 Partnership Agreements: NHS Act 2006 - integrated budgets

External Links and References

- Department of Health (2000) The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health.

- Field, J. and Peck, E. (2003) 'Mergers and acquisitions in the private sector: what are the lessons for health and social services' in: Social Policy and Administration, Vol. 37(7): 742-755.

- Glasby, J. and Peck, E. (eds) (2003) Care Trusts: partnership working in action. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press.

- Glasby, J. and Peck, E. (2004) Integrated Working and Governance: a discussion paper. Leeds: Integrated Care Network.

- Glasby, J. and Peck, E. (2005) Partnership working between health and social care: the impact of Care Trusts. Birmingham: Health Services Management Centre.

- Peck, E., Gulliver, P. and Towell, D. (2002) Modernising Partnerships: an evaluation of Somerset’s innovations in the commissioning and organisation of mental health services – final report. London: Institute of Applied Health and Social Policy, King’s College.