(Shared) Funding

commissioning and contracting with individual or pooled budgets

Keywords: partnership working, pooled budgets, integration, legislation

Section 75 Partnership Agreements: NHS Act 2006 - integrated budgets

Summary

Section 75 partnership agreements, legally provided by the NHS Act 2006, allow budgets to be pooled between local health and social care organisations and authorities. Resources and management structures can be integrated and functions can be reallocated between partners. Legal mechanisms allowing budgets to be pooled (the section 75 partnership agreement) are thought to enable greater integration between health and social care and more locally tailored services. The legal flexibility allows a strategic and arguably more efficient approach to commissioning local services across organisations and a basis to form new organisational structures that integrate health and social care. This practice example reviews the function and impact of Section 75 partnership agreements and covers different local approaches to restructuring services.

What is the main benefit for people in need of care and/or carers?

Flexibility across health and social care budgets can allow resources to be used where they are most needed. For instance health money could be used for preventative community services.

What is the main message for practice and/or policy in relation to this sub-theme?

The legal freedom for partners to pool their budgets has the potential to make service design more tailored to local population needs. Organisations have used budget pooling in different ways and evidence suggests that forming new joint structures can take a lot of time and commitment.

Why was this example implemented?

Legal mechanisms allowing budgets to be pooled are thought to enable greater integration between health and social care and more locally tailored services. The arrangements allow commissioning for existing or new services, as well as the development of provider arrangements, to be joined-up. They were previously referred to as Section 31 (1999) Health Act flexibilities.

A clear gap filled by the work underpinned by Section 75 partnerships is the gap in the patient care pathway. Integrated structures serve to reduce problems in transition between service providers e.g. intermediate care services.

The specific objectives for implementing Section 75 agreements are:

- to facilitate a co-ordinated network of health and social care services, allowing flexibility to fill any gaps in provision

- to ensure the best use of resources by reducing duplication (across organisations) and achieving greater economies of scale; and

- to enable service providers to be more responsive to the needs and views of users, without distortion by separate funding streams for different service inputs.

Learning disability services are the type of provision most commonly grounded through use of Section 75 agreements. Councils tend to host these services after the transfer of funds from NHS Trusts. However there are several examples of integrated provision locally tailored towards older people, this often takes the form of community-based multi-disciplinary nurse-led teams and equipment.

Description

Section 75 partnership agreements, legally provided by the NHS Act 2006, allow budgets to be pooled between health and social care planners/providers, resources and management structures can be integrated. Most NHS Trusts, Care Trusts and councils have some form of pooled funding arrangements, with pooled funds amounting to around 3.4% of the total health and social care budget.

Legislation was drafted nationally and followed on from the previous (1999) Health Act. Joint working and the use of legal flexibilities, such as the Section 75 Partnership Agreement, were encouraged through national policy agendas such as World Class Commissioning, ‘Strong and Prosperous Communities’ (2006), ‘Our Health, Our Care, Our Say’ (2006), ‘Putting People First’ (2007) and ‘Transforming Community Services’ (2009). Integrated provision structures scored highly in World Class Commissioning assessments (partnership working is a key competency), providing localities with further incentives to build joint structures within health and social care.

At a practical level NHS and local council managers and directors are directly responsible for initiating and developing the partnership agreements. This involves an often lengthy process of local negotiation resulting in a new legally binding partnership framework agreement. Arrangements can also be complex, requiring careful consideration to reach clarity around accountability and governance frameworks.

Within LTC it is community services rather than residential care settings that have most potential to be developed through pooled budgets and joint action plans. Through joint structures with pooled finance, multidisciplinary nurse-led teams have been established to support older people living in the community. Such services have been seen to enhance access to community health professionals such as physiotherapists and speed up the assessment process and distribution of assistive technologies within people’s homes.

There is much consensus that setting up a partnership agreement and implementing organisational change is a complex, labour intensive task often involving initial tensions of organisational cultures whilst roles and responsibilities are redefined. However, evidence of efficiencies gained by forming single structures gives incentives to embark upon the route of pooling budgets and forming joint structures.

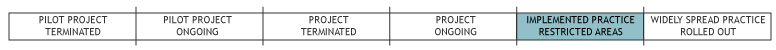

The development of new services and organizations based on Section 75 has been ongoing since 1999. This activity occurs at a local level.

What are/were the effects?

Evidence from the UK around integration remains limited and focused on process rather than outcomes. Despite this there are promising indications from individual projects that joint working leads to positive outcomes for service users.

The impacts of integration have been highly commended in localities and include: improved accessibility to intermediate care, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and district nurses; faster rates of assessment, provision of care and installation of home equipment; and reduced use of acute hospital services. Impact evaluations have been piecemeal including: independent evaluation and commentary e.g. the Audit Commission; individual project evaluations; local government assessments and outcome data.

One example of efficiencies created through joint structures can be seen in the city of Liverpool, where a single commissioning unit was created using a Section 75 partnership agreement. Back office savings are estimated to be around €1.5 million per annum. These savings result from shared systems and overheads used by the integrated unit team. The location of the team in shared premises, single health IT system, single performance management system and aligned indicators and shared outcome goals contribute to more efficient and focused working practice.

Another example of impact can be seen in the locality of Knowsley’s Health and Wellbeing board, with a pooled budget and joint commissioning activity. The approach has allowed a significant level of flexibility around use of resources. For instance, NHS funds have been used to support community projects which target the causes of local health inequalities. By shifting health budgets into community services the preventative potential of these flexibilities can be seen.

In another northern town, Barnsley, the local council and health authority pool their budgets and have reorganised their services for older people into an integrated commissioning level and an integrated provider level. The Council take a lead in the commissioning of services and the health authority lead the provision. The area have received excellent inspection reports for their services, including a drop in the ratio of older people admitted on a permanent basis to residential or nursing care.

What are the strengths and limitations?

The legal flexibility to pool budgets provides a clear opportunity for local health and social care organisations to form integrated services. The legislation is versatile, leaving localities to shape new systems of governance and provision to suit the capacity of local partners and the needs of their populations. Local evidence suggests that integrated management structures and services have several beneficial outcomes for users and can make efficiency savings by avoiding duplication.

A weakness in current arrangements is the time-intensive nature of setting up a Section 75 partnership agreement. Managers report that paperwork can be demanding and strong and dedicated leadership is needed to steer localities through such restructuring processes.

The Audit Commission (2009: 19) observe that one possible reason for the absence of formal joint financing arrangements is that the provision of social care is means-tested. Charging is most common for older people’s services. Although there is no legislative barrier to service integration where charging for the council element is involved, partners need to be clear on the mechanics of these arrangements. This complication thus providing a disincentive to pooled funding options.

Both the sustainability of existing partnership agreements and a simplification of procedures needed to establish partnerships are promised in the Department of Health white paper (2010). Many of the efficiencies and user outcomes covered in this example relate to the new integrated management structures and services. Setting up a Section 75 partnership agreement is currently the process that enables such services to be established. However, feedback from actors suggests that there is scope for the process to be simplified and improved.

Credits

Author: Kerry AllenReviewer 1: Ricardo Rodrigues

Reviewer 2: Laura Cordero

Verified by:

Links to other INTERLINKS practice examples

External Links and References

- Allen, K., Glasby, J. and Ham, C. (2009) Integrating Health and Social Care: a rapid review of lessons from evidence and experience. Birmingham, HSMC

- Audit Commission (2009) Means to an end: joint financing across health and social care. London, Audit Commission

- Communities and Local Government (2008) 'Creating strong, safe and prosperous communites: statutory guidance’

- Department of Health (2006) ‘Our health, our care our say’

- Department of Health (2010) ‘Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS’

- Department of Health (2009) Transforming Community Services: enabling new patterns of provision

- Dickinson, H. (2008) Evaluating outcomes in health and social care. Bristol, The Policy Press Glasby, J. and Dickinson, H. (2008) Partnership working in health and social care. Bristol, Policy Press

- HM Government (2007) Putting people first: a shared vision and commitment to the transformation of adult social care. London, HMSO

- Ham, C. (2009) Only connect: policy options for integrating health and social care (briefing paper prepared for The Nuffield Trust). London, The Nuffield Trust