Governance Mechanisms

a description of steering mechanisms concerning access and eligibility criteria

Keywords: innovative care among /towards Alzheimer patients, Governance of national pilot, Multi level Consensus building, Interagency cooperation, Multi professional coordination

Governing the building process of care innovation for Alzheimer patients and their families: the MAIA national pilot project

Summary

This examples describes the governing process and first results of a national pilot programme targeting Alzheimer patients and their families and aiming to efficiently address their complex needs. The programme brings together all organisations and professionals involved in the care of the target population in a specified area. Using a consensus building methodology, all stakeholders have to build a new type of interagency and professional care collaborative in order to achieve the following outcome: whatever the point of entry in the new organisation, each patient should be cared for in a similar way by optimising all local resources.

So the collaborative can be defined as a ‘multiple entry point’ on a functional level but was termed Maison pour l’Intégration et l’Autonomie des malades Alzheimer (Houses for the autonomy and integration of Alzheimer patients) by MAIA. It represents one of the ten core goals of the 2008/2012 French Alzheimer Plan which is one policy priority of President Sarkozy.

Another measure, embedded in the previous one, consists of implementing a case management programme targeting patients and families with complex needs in each MAIA.

The governance of the programme relies on its active follow-up by a specific team in order to facilitate the implementation process which is acknowledged by a ‘national quality label’ if the results are positive.

The example describes the building process, the follow-up and first results of the assessment. Main lessons come from the analysis of the interactions between the supervising team and the 17 local settings that were particularly chosen to support the implementation of MAIA. Other lessons learned included how the political constraints linked to the programme hampered or helped the overall building process and could impact on its potential transferability.

What is the main benefit for people in need of care and/or carers?

The assessment process is still ongoing. It focuses mainly on process (integration of services at three levels) and on direct outputs for older people based on indicators such as: rate of within 30 days delay rehospitalisation; level of drugs prescription.

Evidence regarding the impact on carers cannot be expected until 5 years after implementation and will be based on indicators such as: access improvement to appropriate services (easier and timelines), carers satisfaction and quality of life.

What is the main message for practice and/or policy in relation to this sub-theme?

Being part of a national pilot with the availability of extra funds and the existence of a scientific evaluation led by a national expert team are strong facilitating factors to speed care innovations. But this may come at the price of “experimental bias” and also on not letting enough time for assessing the national pilot.

In this regard it is also important to find the best balance between local champion’s expectations and national team priorities, especially regarding each stakeholder’s agenda with the former searching for a longer time frame in order to overcome resistance to change while the latter have a more restricted calendar linked to the political agenda. Finally, extra funding may still be required although once mainstreamed these new organisations are not supposed to receive additional funds.

Warum wurde diese Initiative implementiert?

Evidence exists of important gaps in the way Alzheimer patients and their families were informed, supported and transferred between coordinated professionals. The latter was due to provider organisations working independently and supervised by agencies that were poorly connected, thus leading to sub-optimal care.

The aim of this pilot experiment, governed at the national level and supervised by a team of three high ranking civil servants and two public health researchers, was to overcome the above mentioned deficits. The consensus building process was based on the Prisma model (Hébert et al, 2010) and took place at three levels: strategic/political (inter agency), operational (providers) and delivery (professionals) in specific geographical areas.

The chosen experimental design was a mix of a bottom up and top down approaches. It relied firstly on the local dynamics of all voluntary organisations and professionals steered by a champion, in order to boost the process of re-engineering care delivery. The use of a common national framework allowed the chosen settings to share their mutual experience for optimising their resources. The latter approach was also considered useful to ensure ‘geographical equity’ and achieve a ‘national quality label’.

The supervising team of the programme pilot had two interwoven missions. These were to facilitate the development of a common culture through experiences and knowledge transfer between the 17 experimental sites, while periodically assessing each of them using a common evaluation methodology.

Beschreibung

Seventeen settings were chosen among 100 possible sites to reflect diversity regarding geographical location (rural/rural-urban/urban); provider level; area covered; and prevalence of the 60+ population. In each setting, the overall re-engineering process was designed to ensure that, independently of their entry point (either through professionals or providers or agencies), patients and their families’ needs would be processed equally using all available resources. This meant that they would be provided with the same information and advice, and if necessary be assessed and entitled to a care plan as well as supported and followed up in similar ways. In each setting, a coordinator responsible for the development of the consensus approach to care would bring together all decision-makers and funding agents at each level so they could reach an initial diagnosis. This would include identifying existing met and unmet needs; how each provider met the needs; gaps and links in interagency working and professional coordination; and missing resources (in cash and in kind). All participants would then define the main priorities and set up common policies and programmes with appropriate funding. They would agree upon multidisciplinary assessment tools, on rules to set up the corresponding care plan and upon information and data flow. New pathways resulting from service re-organisation would be defined and implemented at an operational level and new care processes at delivery level. Criteria for selecting patients who were entitled to case management had to be set up.

The programme began in mid 2008 with a follow up of the overall development process during 2009. Case management implementation was carried out from October 2009 to March 2010 and the evaluation of the pilot up to December 2010 with regular (six times per year) meetings promoting mutual exchange between the national team and all sites. Cost: CNSA (National Agency for Disability Policy) paid each site an annual amount of €100,000 and case manager (67) wages amounting to €50,000 per year. Annual costs for the national team were €350,000. The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs paid for the costs of the pilot evaluation which amounted to €150,000 per year.

Welche Effekte wurden erzielt?

Evaluation methodology

A semi structured MAIA scale was used to measure the strength of the collaborative work at each level and the extent to which all stakeholders were united in the same goal. Examples of indicators were number, type and frequency of encounters between stakeholders; main issues tackled and solved; creation of new ‘entry points’; choice and use of common assessment tools, impact on care plan protocols; and progress towards an electronic data flow. With reference to the implementation of the case management programme, the number of Case Managers and caseloads were measured.

The local context was assessed using focus groups involving project coordinators and case managers, individual interviews with case managers and champions, and observation of the multiple entry point implementation process.

Main Results

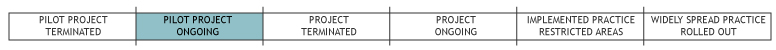

- Among 17 settings, 12 were considered on target, with seven having recommendations for improvements. Major concerns were raised in three of them, with recommendations to be urgently addressed. Two were stopped.

- ‘Small area’ settings seemed to progress faster than settings involving the highest strategic level (general council).

- Work done at provider rather that at strategic level appeared central. The development process was easier when the champion did not act as a front runner and worked in collaboration with other stakeholders. Ideally she/he would support the coordinator to perform his tasks by helping to solve conflicts in a smooth fashion at the strategic level.

- Multi entry point functioning had more chance of success without the involvement of organisations having similar approaches. They tended to be resistant to change regarding the involvement of other participants.

Regarding multi-dimensional assessment tools, one setting chose RAI, eight chose SMAF (Gervais et al, 2010) and eight chose Geva.

Regarding case managers, 35% were social workers, 31% nurses; 21% psychologists; and 7% occupational therapists. The number per site ranged from two to nine and the average case load from 15 to 30. They considered professional exchange and team working as strong tools to combat fragmentation of care. Involvement of families was poor.

Worin bestehen die Stärken und Schwächen der Initiative?

Strengths

- Being part of a national programme with strong policy support.

- The consensus building framework through the work done on multiple entry point issues and case management.

- Knowledge and experience exchange; an active follow up and assessment by the national team.

Weaknesses

- Power issues and territorial conflicts at all levels linked to different backgrounds, goals and cultures.

- The complexity of the three level consensus building process. For example lack of legitimacy of coordinators at the operational but also at strategic level could be detrimental when champions were not perceived as strong enough to provide the necessary psychological support and back-up.

- Too much administrative time and paperwork requested for the follow-up and the evaluation.

- Gaps between local champion’s expectations and national team priorities: the latter was caught in time constraints linked to the project political agenda while the former looked for a longer time framework in order to overcome resistance to change.

- Poor involvement of families; lack of assessment of their satisfaction and quality of life.

Opportunities

- The new regional agency set up in April 2010 is now accountable for the MAIA implementation process and will be given some steering capacities. So they may reinforce the overall building process as 100 MAIA are expected for year 2011, the pilot being prolonged for one year.

Threats:

- The existence of a scientific evaluation; being part of a national pilot; availability of extra funds were considered strong facilitating factors (experimental bias). However funding may still be required as once mainstreamed, initiatives like this do not receive additional funds.

Impressum

Autor: Michel NaiditchReviewer 1: Stephanie Carretero

Reviewer 2: Lis Wagner

Verified by:

Links zu anderen INTERLINKS-Initiativen

Externe Links und Literatur

- National Pilot project MAIA

- Alzheimer Plan

- Maia case manager program

- Geva

- Rapport Menard

- Hébert R, Raîche M, Dubois M-F, Gueye NR, Dubuc N, Tousignant M, and the PRISMA Group (2010) 'Impact of PRISMA, a coordination-type integrated service delivery system for frail older people in Quebec (Canada): A quasi-experimental study' in: Journals of Gerontology-Series B: Social Sciences, Vol. 65B: 107-118.

- Maia Assessment Report: DGS URC HEGP 12/2010

- Gervais P, Hébert R, Tousignant M. (2010) 'Méthodologie de l’étude d’évaluation de l’implantation du Système de Mesure de l’Autonomie fonctionnelle (SMAF) dans le secteur médico-social français: l’étude PISE-Dordogne' in: Revue de Gériatrie, Vol 35, No 4: 235-244.