Discharge, terminating professional contacts

how information (files, care plan) and responsibilities are transferred (logistics issues)

Keywords: Team work, Integration, Professional culture, Hospital discharge, Health and social network

Coordinating Care for Older People (COPA): Team work integrating health and social care professionals in community care

Summary

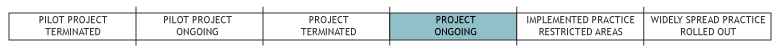

The example took place within the 16th Paris Borough as a pilot research action programme promoted by the public health department of St Quentin University. It consists of two programmes: the long term case management programme (LTCM) and the temporary case management care programme (TCMP). In both programmes, the care of each recruited person is managed by a team led by a case manager and the corresponding primary care physician (PCP). Goals are to allow the target population (frail older people living in the community) a longer but safer home stay while limiting hospitalisations via Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments but also to optimise hospital discharge.The network involves all voluntary health and social organisations (nursing homes, nursing and home help agencies) located in the catchment area of the university hospital St Perrine as well as voluntary self-employed health and social professionals. All of them, including managers, participated in the development of main principles underpinning new care pathways to be implemented by the new multidisciplinary primary and secondary care and social network. The example shows it is possible through a specific design to locally foster a common culture leading to interprofessional and institutional agreements regarding the content and implementation of new care pathways that can fill the gaps between health and social professionals.COPA succeeded in reducing the overall rate of hospitalisation, also via A&E. But even though the initiative was built on sound principles, it did not perform better than routine networks or routine care with respect to institutionalisation or death. COPA is still on-going and has been only partially replicated in one city of South France (Marseille).

What is the main benefit for people in need of care and/or carers?

The benefit for older people is a lower rate of hospitalisation through the emergency room (but with no change in mortality or rate of overall hospitalisation). Also, they can achieve an enhanced quality of life with less depression. For carers there has been no direct significant effect on quality of life as they are not involved in the care process design.

What is the main message for practice and/or policy in relation to this sub-theme?

In order to overcome GPs' potential opposition in changing their clinical practice, it is possible to meet the primary care physicians' expectations through a well-designed bottom-up approach, for example by providing resources to care for their most complex (and thus time consuming) patients. However, in practice such a process is time consuming and needs investments and strong promoters as well as a continuous commitment of all involved professionals.

At policy level, even a rather successful pilot experiment needs strong support from decision-makers to gain national coverage and support and to be rolled-out nationally. In this regard, a well-designed cost-efficiency analysis should be part of the overall assessment as it constitutes a strong argument.

Warum wurde diese Initiative implementiert?

National as well as international surveys consistently demonstrate that frail older people living in the community are at high risk of experiencing adverse events such as unnecessary hospitalisations via A&E departments. These deficits correlate with a lack of communication and coordination between hospital and primary care professionals such as nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, home helps and social workers leading to poor continuity of care. The goal of COPA was to construct new agreed pathway and care processes through a specific experimental design in order to reduce and/or prevent the above mentioned deficits. Institutionalisation and mortality rates were expected to become lower as frail older people remained safely in their homes for a longer time period and with a good quality of life. Securing the participation of PCPs was considered a key element for success. The feasibility period with eight focus group sessions revealed five features of the proposed model:

- PCPs would have the final responsibility for all decisions.

- They would be backed up by case managers (CMs) for their more complex patients.

- Integration of specialised care would be achieved through outreach visits by hospital based geriatricians who would also help with reducing hospitalisation through visits in the A&E departments.

- CMs and geriatricians would fill all information gaps between hospital staff and PCPs during the patient’s stay while involving patients and families in discharge management planning in an improved way.

Beschreibung

The overall pilot developed under the supervision of two public health physicians located in the University hospital. The process involved another private hospital and all voluntary health and social agencies in the vicinity, as well as self-employed professionals caring for older people. Recruitment of the target population was based on common agreed criteria and assessment tools (RAI-HC).

The building process led to two case management programmes. Under the LTCM, care is provided to patients from selected PCPs (with 50% of their listed clients aged 65 years or more). They are pro-actively recruited based on a review of their medical charts done jointly by CM and the referring physician. Regarding the TCMP, recruitment is passive through referrals of patients' informal carers from other PCPs when they consider the former to be overburdened. The programme stops when they consider the crisis is over. One case manager (nurse) is assigned to each PCP, each one working on average with 10 PCPs and managing 40 patients. After a patient has been assessed by his CM, the latter meets with or contacts the multidisciplinary team by telephone in order to discuss the care plan which has to be consistent with patients’ needs and expectations and with available resources. The case manager then meets the referring PCP at his practice in order to: discuss and improve the care plan, set priorities together and decide which evidence-based protocols will be used. The CM then implements and coordinates health and social services across the different settings and among care providers while informing his informal carers. He takes main responsibility for following-up and reassessing patients every three months or more if needed and can be reached at any time by all professionals, patients and family members. He also organises inpatient visits and hospital discharges with the hospital team and informal carers.

The initiative lasted 6 years (2004-2009). The cost of the feasibility period (2 years) was €75,000 including training. The comparative evaluation funded by HAS (NICE equivalent) and CNSA (National Agency for Disabled Population policy) amounted to €200,000 over 4 years. Specific functioning costs included part of the salaries of the three CMs, two geriatricians plus compensation for 175 participating PCPs amounting to €200,000 per year. The control groups received their usual budgets.

Welche Effekte wurden erzielt?

The 18 months for the programme implementation led to a 21 month recruiting period with a 12 month follow-up for each patient. Among them, 249 older people were screened as potential COPA users, with only 110 (44.2%) meeting all inclusion criteria and finally 106 (96.4%) who were able to give direct consent or through proxies entering COPA: this included 73 (69%) through LTCMP and 33 through TCMP. Overall they represent a group of very frail older people with an average age of 86; a high level of needs (as measured at recruitment according to Chip+ score based on RAI-HC) each of them corresponding to a specific but complex mix of ADL/IADL impairments associated with cognitive deficit, isolation and multi-morbidities.

This group was quasi experimentally compared with two controls. The first one corresponded to patients recruited from their home and belonging to a ‘genuine geriatric network’ where coordination between all mainstream providers of home help, nursing care and self employed professionals was the responsibility of a nurse who did not benefit from direct access to the hospital geriatrician and had to hospitalise patients through the A&E department. The second contained patients recruited at discharge and receiving usual home care (where informal carers are implicitly ‘care coordinators’).

Main outcome criteria concerned hospital service utilisation as measured by the following indicators:

- Number of hospital (re)admissions through (or not) Accident and Emergency room visits,

- Ratio of planned/unplanned hospital stays. Secondary indicators included: physical and cognitive status (assessed 0, 6 and 12 months after inclusion),

- Use of home care services, institutionalisation and death rates; user’s satisfaction and quality of life (but not caregiver’s burden),

- PCP’s opinions of the initiative through interviews.

Main results:

- The rate of hospitalisation was significantly lower in COPA compared to the second control while hospitalisation through A&E was significantly lower than in the first one.

- COPA patients were more (not significantly) institutionalised than in both groups but had similar death rates.

- Regarding other outcomes, results were mixed but overall better in COPA. Physician’s enrolment in COPA grew as did their use of evidence based practice.

- Analysis of COPA users showed overall positive results: similar health status but enhanced quality of life with less rates of depression. The evaluation showed no significant effect on carer’s satisfaction nor involvement in care choices.

- No assessment of cost-efficiency was completed.

Worin bestehen die Stärken und Schwächen der Initiative?

Strengths

- The organisation’s principles were tailored through a participative developmental process which met PCPs expectations thus overcoming their potential opposition. This was because the care model provided them with specific resources for caring for their most complex (and thus time-consuming) patients.

- The example shows some evidence of success regarding reduced hospitalisation (total rate and through A&E visit).

Weaknesses

- This type of developmental process needs strong leadership and expertise and a continuous commitment from professionals. Thus time and cost investments are needed. COPA did not bring positive results regarding adverse events other than hospitalisations (such as a better health status, less institutionalisation or delayed mortality). This may relate to the choice of the target population which was more complex and frail than the control group with respect to isolation and the rate of multi-morbidities (see also opportunities).

- In this professionally lead experiment neither older people nor informal carers were involved or empowered.

Threats

- As it is often the case for successful local pilot experiments, strong support from decision-makers is needed in order to spread. So even if support from nationally well recognised health agencies (such as HAS and CNSA) was key to funding and assessing the example, the lack of local political support endangers its ability to further develop in spite of national coverage and back-up.

Opportunities

- Nurturing local professional dynamics by involving them in the building process of a new teamworking approach was a key ingredient for success. So some extra rewards for participants (not necessarily based on financial incentives) could also be useful to maintain and sustain the local dynamics.

- As the new (April 2010) regional health agencies are supposed to plan, finance and regulate both health and social care sectors, they may help in promoting and financing this type of interagency working.

- Targeting a less frail population of older people (either not yet disabled and/or not yet suffering from chronic conditions) may enhance the odds of a more efficient and preventative type of intervention.

Impressum

Autor: Michel NaiditchReviewer 1: Teija Hammar

Reviewer 2: Ina Diemanse

Verified by: Matthieu de Stampa

Links zu anderen INTERLINKS-Initiativen

- Follow-up home visits after discharge from hospital

- Integrated home care and discharge practice for home care clients (PALKOmodel)

Externe Links und Literatur

Policy evidence

- Hofmarcher M, Oxley H, Rusticelli E (2007) Improved Health System Performance through Better Care Coordination. Paris: OECD Health Working Papers, 30.

Main sources of evidence

- de Stampa M, Vedel I (2010). Impact de la coordination sur l’état de santé les pratiques professionelles et le recours aux service pour les personnes âgées dépendantes vivant à domicile. Rapport de l’expérimentation COPA.

- de Stampa M, Vedel I, Mauriat C, Bagaragaza E, Routelous C, Bergman H, Lapointe L, Cassou B, Ankri J, Henrard JC (2010). 'Diagnostic study, design and implementation of an integrated model of care in France: a bottom-up process with continuous leadership' in: Int J Integr Care, 10:e034.

- de Stampa M, Vedel I, Bergman H, Novella JL, Lapointe L (2009) 'Fostering participation of general practitioners in integrated health services networks: incentives, barriers, and guidelines' in: BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 9:48.

- Vedel I, De Stampa M, Bergman H, Ankri J, Cassou B, Blanchard F, Lapointe L (2009) 'Healthcare professionals and managers' participation in developing an intervention: a pre-intervention study in the elderly care context' in: Implement Sci, vol. 4(1):21.

Similar other practice examples

- Béland F, Bergman H, Dallaire L, Fletcher J, Lebel P, Monette J, Denis J-L, Contandriopoulos A-P, Cimon A, Bureau C et al (2004): Evaluation du système intégré pour personnes âgées fragiles (SIPA) : utilisation et coûts des services sociaux et de santé. Edited by Foundation CHSR.

- Beland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Clarfield AM, Tousignant P, Contandriopoulos AP, Dallaire L (2006) 'A system of integrated care for older persons with disabilities in Canada: results from a randomized controlled trial' in: J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 61(4):367-373.

- Eklund K, Wilhelmson K (2009) 'Outcomes of coordinated and integrated interventions targeting frail elderly people: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials' in: Health Soc Care Community, 17(5):447-458.

- Kodner DL, Kyriacou CK (2000) 'Fully integrated care for frail elderly: two American models' in: Int J Integr Care, vol. 1:1-28.